The Lost Epicureanism of Charles Bukowski, the Street Lucretius

"So, when our mortal flame shall be disjoined / The lifeless lump uncoupled from the mind / From sense of grief and pain we shall be free / We shall not feel, because we shall not be."

Charles Bukowski is alternately remembered as a brilliant American writer who catalogued the gutter of the 20th century in undeniably compelling ways, and as a misogynistic drunkard whose cheap tricks on the page did not make up for his selfish and contemptible behavior.

There is a similar split on Epicureanism, which is seen by some as a hedonistic cult and by others as a prudent philosophy for living a good life.

But like the Epicureans, trying to label Bukowski as an irredeemable pleasure-seeker is reductive. In his novels, short stories, poems, and interviews, one finds many parallels to the main tenants of Epicureanism: the glories of simplicity, the false promises of the rat race, and the fulfillment found in living authentically for yourself.

On Death

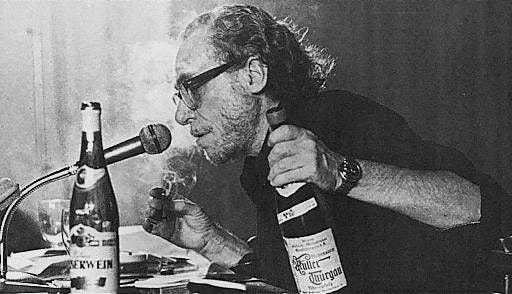

In a 1978 interview with the French literary talk show Les Apostrophes, Bukowski struck an indifferent and even hopeful tone about death.

Bukowski: I almost feel good at the approach of death.

Interviewer: Why? You have a nice wife.

Bukowski: All that's okay. But you see, as you live many years, things take on a repeat. Has that ended? Are you ended? No, no, it's okay. Things take on a repeat. You understand? You keep seeing the same thing over and over again, the same substance, the same action, the same reaction. So you get a little bit tired of life. As death comes, you almost say, “Okay baby, it's time.” It's good. So I have very little fear of death. In fact, I almost welcome it.

Epicureans were materialists who took a similarly straightforward view of death: While you live, you are alive, so need to worry. And when you die, you’ll be dead, so no need to worry.

Take this from Epicurus’ letter to Menoeceus:

Accustom yourself to believe that death is nothing to us, for good and evil imply awareness, and death is the privation of all awareness; therefore, a right understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not by adding to life an unlimited time, but by taking away the yearning after immortality. For life has no terror; for those who thoroughly apprehend that there are no terrors for them in ceasing to live.

Foolish, therefore, is the person who says that he fears death, not because it will pain when it comes, but because it pains in the prospect. Whatever causes no annoyance when it is present, causes only a groundless pain in the expectation. Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not. It is nothing, then, either to the living or to the dead, for with the living it is not and the dead exist no longer. But in the world, at one time people shun death as the greatest of all evils, and at another time choose it as a respite from the evils in life.

Epicurus founded his school, "The Garden," in 307 BC in Athens. A skeptic of religious dogma and social authority, he taught that one can live a tranquil life through simplicity and minimalism, taking care to avoid politics and the status trappings of the fast life. Happiness (εὐδαιμονία, eudaimonia) is attained not through the maximization of pleasure, but by being free from mental stress, (ἀταραξία, ataraxia), and the absence of physical pain (ἀπονία, aponia).

Because only a few letters and fragments survive from the 300+ works that Epicurus authored, the Epicurean philosophy is best illustrated by the great Roman poet Lucretius, the namesake of this publication, who wrote On the Nature of Things in the 1st century BC.

In Book III of Lucretius’ masterpiece, he illustrates the folly of fearing death. From John Dryden’s beautiful 1685 translation:

For, if thy life were pleasant heretofore,

If all the bounteous blessings I could give

Thou hast enjoyed, if thou hast known to live,

And pleasure not leaked through thee like a sieve;

Why dost thou not give thanks as at a plenteous feast,

Crammed to the throat with life, and rise and take thy rest?

But, if my blessings thou hast thrown away,

If undigested joys passed through, and would not stay,

Why dost thou wish for more to squander still?

If life be grown a load, a real ill,

And I would all thy cares and labours end,

Lay down thy burden, fool, and know thy friend.

Bukowski’s sentiment on death, “I almost welcome it,” is a clear echo of Lucretius’ urging to “give thanks as at a plenteous feast” then “rise and take thy rest,” and for us to “know thy friend [death].”

Dryden’s translation of Book III continues:

What has this bugbear, death, to frighten men,

If souls can die, as well as bodies can?

For, as before our birth we felt no pain,

When Punic arms infested land and main,

When heaven and earth were in confusion hurled,

For the debated empire of the world,

Which awed with dreadful expectation lay,

Sure to be slaves, uncertain who should sway:

So, when our mortal flame shall be disjoined,

The lifeless lump uncoupled from the mind,

From sense of grief and pain we shall be free;

We shall not feel, because we shall not be.

The French philosopher Montaigne’s translation may be closest to the original Latin for this key line: “Why not depart from life as a sated guest from a feast?”

On Life

But what of life? Epicurus tells Menoeceus that by shedding our fear of death, we can become like gods.

Exercise yourself in these and kindred precepts day and night, both by yourself and with him who is like to you; then never, either in waking or in dream, will you be disturbed, but will live as a god among people. For people lose all appearance of mortality by living in the midst of immortal blessings.

In Bukowski’s poem The Laughing Heart, he tells us that “you can't beat death but

you can beat death in life, sometimes,” and that when you live an authentic life, “the gods wait to delight in you.”

your life is your life

don't let it be clubbed into dank submission.

be on the watch.

there are ways out.

there is a light somewhere.

it may not be much light but

it beats the darkness.

be on the watch.

the gods will offer you chances.

know them.

take them.

you can't beat death but

you can beat death in life, sometimes.

and the more often you learn to do it,

the more light there will be.

your life is your life.

know it while you have it.

you are marvelous

the gods wait to delight

in you.

No one escapes death, but if we live a full and authentic life now—with no fear of what’s to come or creeping regret about the past—then we “lose all appearance of mortality by living in the midst of immortal blessings,” as Epicurus put it.

In another poem, Pernicious Anemia, Bukowski again takes a clear-eyed look at life:

I could rest on the past,

there are many books

on the shelves,

the shelves are

overflowing.I could sleep all day

with my cats.I could talk to

my neighbor

over the fence,

he’s 96 and

has had a past

too.I could just flog

life off,

gently wait to

die.ah, what a horror

that would be;

joining the world’s

way.I must mount a

comeback.

I must crawl

inch by inch

back in-

to the sun of creation.let there be light!

let there be me!I will beat

the odds

one more

time.

As Bukowski approached the end of his life, he gave an interview to Life Magazine in 1988 that sums up his Epicurean philosophy well.

For those who believe in god, most of the big questions are answered. But for those of us who can’t readily accept the god formula, the big answers don’t remain stone-written. We adjust to new conditions and discoveries. We are pliable. Love need not be a command or faith a dictum. I am my own god. We are here to unlearn the teachings of the church, state and our educational system. We are here to drink beer. We are here to kill war. We are here to laugh at the odds and live our lives so well that death will tremble to take us.

Crazy how few likes this piece has. Love the epicurean ideas gleaned from Bukowksi’s words. His view on death, certainly, mirrors epicurean ideas. His ideas on moderation though??? But great ideas here.